Names, Names, and More Names by Deborah Beach Giordano

Reading the Bible

A friend wrote in his Christmas card that he was in the process of reading the Bible — the whole thing, cover to cover. His grandfather had done so twice, and Will was feeling an urge to match the old gentleman's record. In this, his first effort, he discovered that the process could be heavy going.

A friend wrote in his Christmas card that he was in the process of reading the Bible — the whole thing, cover to cover. His grandfather had done so twice, and Will was feeling an urge to match the old gentleman's record. In this, his first effort, he discovered that the process could be heavy going.

Like hiking the Appalachian Trail, the idea of reading the entire Bible is a delightful one; the actual process quite demanding: strenuous, even dangerous. There's a lot of strange stuff in there: troubling tales of violence, revenge, deceit, murder, betrayal, bad choices, inexplicable behavior and unpronounceable names.

And I've always that is one of the major impediments to our reading it through: all those strange, confusing names: Nepheg? Zichri and Sithri? sound like exotic musical instruments. Then there's Mushi, and Ithamar, and the list goes on…. Who are these people? Why are they here? Most we never hear of again. And there are so many! It's like at the end of a movie when they run the credits, listing everybody and his cat who were remotely involved (even the caterer); and I'm sure that very few of us read those — unless somebody we know is on there.

“Simeon was the father of Jemuel, Jamin, Ohad, Jachin, Zohar, and Shaul; Kohath was the father of Amram, Izhar, Hebron, and Uzziel….The sons of Korah were Assir, Elkanah, and Abiasaph;...”

Argh! Try saying those ten times, fast. Heck, try saying them at all! And they go on and on. And on.

What We Miss

Maybe these lists were included so we'd understand how the Israelites felt, wandering through the desert for forty years: a loooonnng, dry, dull, apparently pointless journey. They make the text seem so foreign, so ancient, so distant, so unlike us. And I think that’s a pity. As we stumble and bumble and giggle over the curious names, confusion descends like a curtain, closing us off from their very human, as-real-as-today lives.

Because these were real human beings, not strange or unusual: ordinary people living in extraordinary times. And it's very likely they had no idea that those were extraordinary times: to them daily life was ordinary; perhaps going pretty well, or only so-so, or kind of lousy, or even downright miserable — but not remarkable or unusual, nothing beyond the pale; each day was “just another day.” Nobody took any special notice.

What They Missed

Little did they realize that they were in the midst of a divine Inbreaking; that God was with them — an over-arching Presence, every hour, every day. Even less did they realize that Something Serious was afoot, moving within them and among them: a holy Call to freedom. For God is the enemy of oppression, a foe to all pharaohs and would-be pharaohs who seek to control and coerce us; aware, even as His creatures drowse, as chains are forged, link by link.

Lulled by bread and circuses, amused and distracted, the descendants of Jacob's free-range shepherds gradually surrendered their freedoms for the comfort and safety of Egyptian rule.

Then, one day, they awoke to find themselves enslaved.

Ordinary people, doing ordinary things.

The Holy Hum

Throughout, though few heard it, like a honey bee humming among the flowers, God was singing a love song, soft and steady. No matter how far the Israelites strayed from the holy teachings, no matter how dazzled they were by magnificent structures, how deluded by Pharaoh's claim to divine status — God hadn't given up on them.

Throughout, though few heard it, like a honey bee humming among the flowers, God was singing a love song, soft and steady. No matter how far the Israelites strayed from the holy teachings, no matter how dazzled they were by magnificent structures, how deluded by Pharaoh's claim to divine status — God hadn't given up on them.

Perhaps that is who these peculiarly-named characters represent: people who did hear the holy summons, who felt the Divine call resonating in their souls, who continued to believe in God's goodness, despite worldly temptations — and worldly disasters, and who kept praying. These are the ones in every generation who uphold our hope and our lives; people of faith, wisdom, and courage. They are not rich or famous or well-connected, but ordinary people, doing ordinary things in extraordinary times.

Perhaps you are one of them for your generation.

Hidden Holy Ones

Similar to this is the belief in some Jewish circles of tzadikim nistarim. As when God agreed not to destroy wicked Sodom if righteous souls lived there, so, it is believed, God preserves our world for the sake of these people of faith and prayer. They are called the “hidden righteous ones” because no one knows for certain who they are, not even they, themselves — and that's the delightful and slightly disturbing part. Anyone might be one of these hidden holy gems.

The tradition teaches that when one of these faithful ones dies, another is called forth — so a holy hummm sounding out of the blue one morning or evening or whenever is an ever-present possibility.

The tradition teaches that when one of these faithful ones dies, another is called forth — so a holy hummm sounding out of the blue one morning or evening or whenever is an ever-present possibility.

Spot the Hidden Gem

A fun game to play is “Spot the Tzadik.” As you shop for groceries, or while at school or at work, or wherever you are, look at the faces of the people around you: which one might be a hidden holy gem? What about that elderly gentleman in the blue windbreaker? or the cashier with the bright orange hair? the teenager in the grey hoodie? the barista? the lady crossing the street?

Or what about the face in the mirror? You can never know for sure.

Beneath the tradition of tzadikim nistarim is, of course, the reality of the power of faithful folks to uphold the world. As far as literally forestalling armageddon: who knows? But we cannot discount the power — the often literally life-sustaining power of giving comfort to the sorrowing, and strength to the weary, of the uplifting grace of kindness, of simple words, gentle smiles, quick winks and goofy emojis 🥸: “I'm thinking of you,” “You've got a friend,” “I hope you're doing well.” Humane human interaction: the gift of life to life. Greater still, whether declared or even mentioned, is the power of prayer: to bless, to comfort, to heal, to uplift and sustain.

Making the Impossible, Possible

From personal experience and many, many reports, I know that prayer can make the impossible possible, can sustain us when we feel we cannot go on, can give us hope and strength in times of trouble. It can provoke miracles. Prayer can preserve the world, one life at a time. And that is enough.

The more I think about it, the more I like the idea that there are “hidden gems” in these lists of peculiarly-named people: faithful, prayerful, righteous souls who kept the world turning in large ways and small; whose care and kindness to human beings, and passionate devotion to God made life possible in their generations. Ordinary people who were doing (extra)ordinary things — that they didn't consider extraordinary.

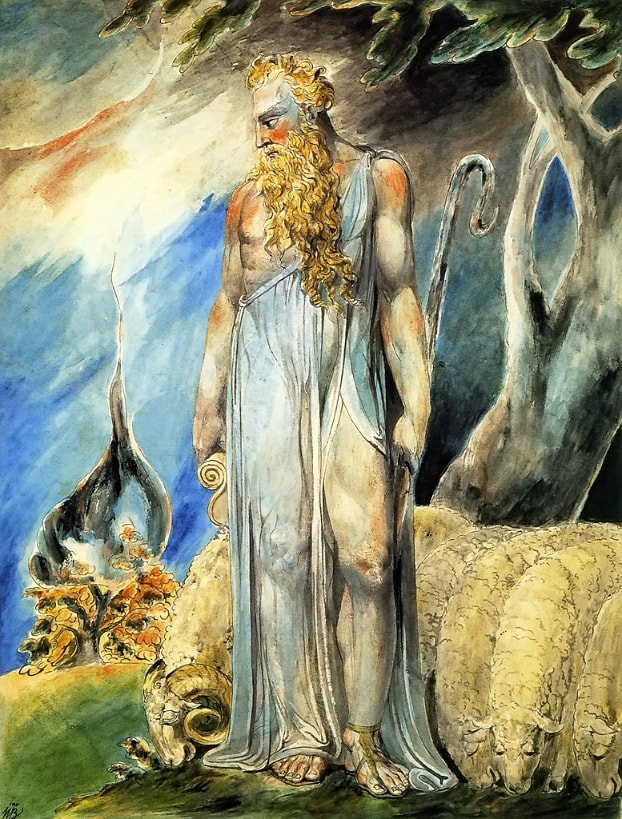

The most significant part of the list in our passage is that it leads to Moses. These may have literally been Moses' ancestors, or they may have been (as I suspect) his spiritual ancestors: God's people — of any and every tribe and type, whose faith kept the world turning, kept courage and hope flowing, so that one day Moses would be born into their community. Further, that through them Moses was raised up to be the kind of exemplary man of faith and courage that he was.

In Plain View

So there it is: in this seemingly dull passage, the Bible shows us that “ordinary people” have extra-ordinary power through simple (?!) faith and prayer; that anyone can overcome the wicked by trusting in God and carrying on with life, refusing to succumb to hopelessness and hate. A dangerous Book filled with dangerous notions, indeed!

May the Radiant One illuminate your understanding,

encourage your spirit,

warm your heart,

and make you dangerous,

Deborah ✝

Suggested Spiritual Exercises

Play “Spot the Hidden Gem” at least once each week.

Live dangerously.